What Lasts

The Most Important Lesson I Have Learned From the Forests -

As upbeat and celebratory as the memorial service for our old friend was, the inescapable sadness was captured in a comment I overheard as I descended toward the sidewalk. Turning to her companion she said "well, I guess he went the way of all things.." Though we're all familiar with this "way of all things" aphorism, hearing it took me aback. Is the phase correct in asserting that the "way of all things" is to inevitably decline and cease to exist, or might there be other options? Join me for an exploration of this question.

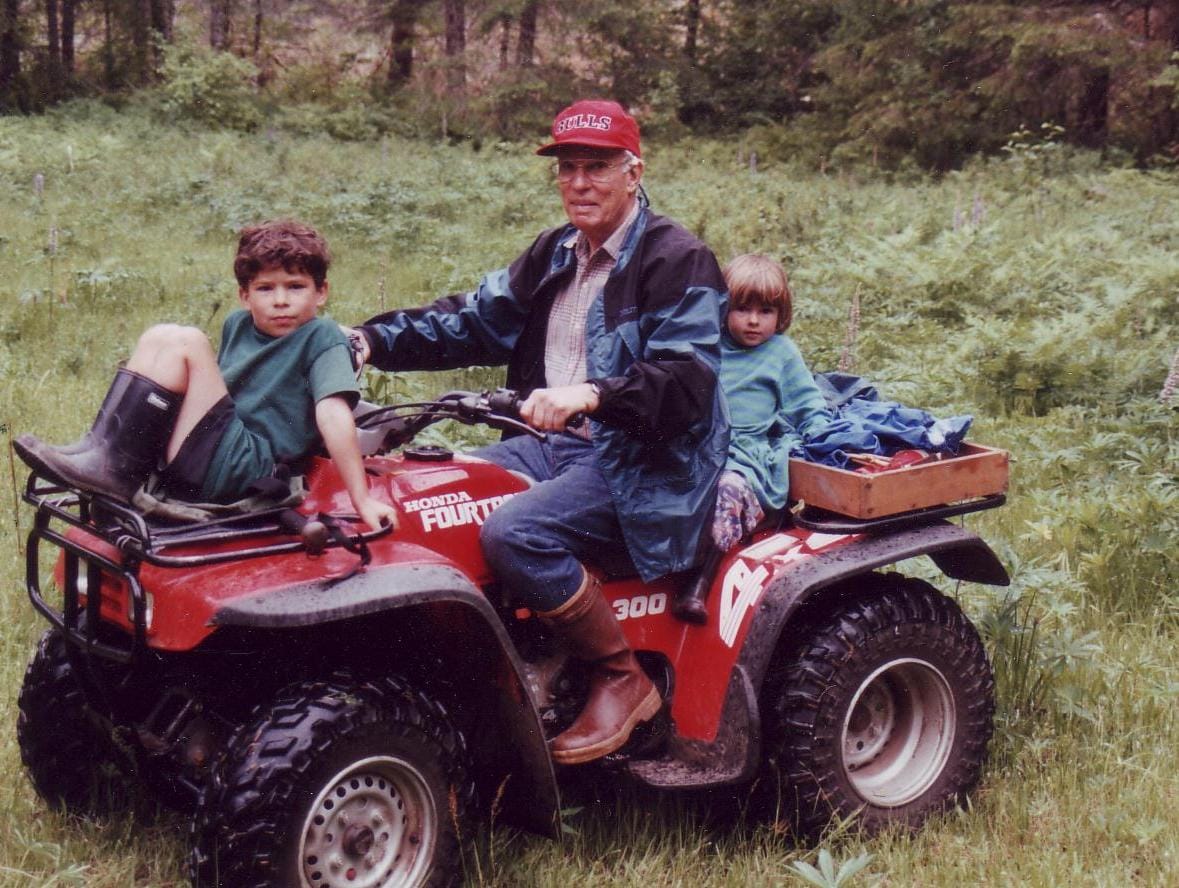

Relationships between people and working landscapes, when they go well and endure over time, lead to inevitable co-evolution. Regardless of whether they are ranches, forests, coastal fisheries, or farms, the places shape our bodies, heads and hearts at the same time that our decisions and actions shape the place. Having paid attention to my own family's working forests in Oregon's Coast Range, and my relationship to them, I know this to be true; I have watched and felt it happen. Of the many ways that our forests have shaped me, the most significant impact is on my thinking. The forests, and my experiences in them, continuously teach me lessons that I find interesting and important. What follows is a description of the discovery that I've found to be most powerful and useful.

Recognition - The new chainsaw was impressive; not only did it start easily and run powerfully, but it was sharp, clean, and fully functional. The enjoyment I felt in falling, bucking, and limbing trees with it was tempered by my awareness that, no matter how well I used and cared for it, it's utility, value, resilience, and adaptive capacity would inevitably decline over its finite lifetime. Eventually I'd be lifting it up to its final resting place on a shelf in the shop beside other "out to pasture", dead saws. I have the same bitter sweet feeling when I see a flower, cut in its prime, placed in a vase on the dining table, or a lithe and powerful, young cross country runner powering over the crest of a hill. Just as with my own body and mind, the future will bring inevitable decline. I think of this as degenerative or downcycle objects or organisms - their utility, value, resilience, and adaptive capacity inevitably decline over time. Life the rising tide or the passage of time, there is not arguing with its inevitability.

With any occupation, we develop an awareness of what tasks and responsibilities sap our energies and enthusiasms and which rebuild them. Through my years of forest work I've developed a sensitivity to this. At the same time that I can lie awake on rainy winters nights thinking of the starter batteries on machinery that will soon need replacement, the truck tires that are nearing the end of their road, or the roofs that should begin leaking too soon, I have become equally aware of aspects of my work in the forests that buck this trend, and recharge my energy and enthusiasm. I consider them regenerative, or up cycle systems because, when either left alone or treated well their utility, value, resilience, and adaptive capacity has potential to increase over time. This discovery has led me to try to reshape our work with and relationship to the forests to minimize the number of down cycle objects and maximize the number and vitality of upcycle systems to build and recharge energy and possibilities instead of sapping them. Note – Because the terms down cycle and degenerative are synonymous as are up cycle and regenerative, communication will be simplified here by using only up cycle and down cycle. Here are two simple examples: when a neighbor clear cuts an area of forest I am mindful of what will happen to that land if humans were to walk away from it for the next fifty years. Given the ubiquitous presence of seed from non native, invasive species, it is all but certain that within three years the land would be dominated by aggressive Scotch broom and blackberry, making it very unlikely that native trees would once again grow on that site for many decades. Logging threw the land into a down cycle state which can only be partially reversed through aggressive intervention –herbicide sprayed and seedlings planted and tended. While the chemicals may help the tiny trees survive, they are killing a wide range of other lifeforms that are important parts of a healthy forest community. Meanwhile, on the other side of the ridge, I can walk through a recently logged section of our forest and experience up cycle conditions. Though valuable trees have been cut and removed, the overall fabric of the forest community is intact. Experience has shown me that if the area is left alone, when we return in five or ten years we will find its value, utility, resilience, and adaptive capacity increased. I'm fortunate to have watched this same power of regeneration in the forests' creeks and wetlands. Based on this learning, our stewardship of the forest is focused on building the most powerful up cycle conditions possible in all parts of the forests, while also working to earn a fair living from the land. Yes, I, like all other individual organisms in the forest, am inevitably down cycle, but that does not keep us from working to leave models of up cycle systems behind us.

Learning though the observation of up cycle and down cycle systems does not end when we drive out through the forest gate. As we travel in any direction we see two unfortunate realities and one fortunate one. The first is that essentially all of the surrounding forest land, with their management shaped by short rotation, monoculture, plantation silvaculture, is in downcycle condition. Though this system may grow significant quantities of low quality wood, for the short term, the land is a net emitter of carbon, growth depends on regular use of herbicides and replanting, and creates uncertainties about the long term health and productivity of the most fundamental resource, soil. Secondly, within this growing sea of downcycle plantations are human communities that have been on downcycle slides for the past five decades. Where there once were vibrant, small, forest-dependent communities we now find abandoned schools with vines growing up past the broken windows and once bustling stores, post offices, and churches either abandoned or converted to residences for the few remaining inhabitants. As options and opportunities diminished, both businesses and people packed up and moved on.

Driving further up the valley our spirits may be lifted by seeing that that human communities, when given the chance, can be just as up cycle as their ecological counterparts. Just as in the forest, all individual elements are inevitably mortal - Dr. Smith, principal Larson, Mayor Nagisaki, and Max Ragen the electrician will all eventually retire, die and be buried up on the hill, but, if the conditions are right, the community will either spawn or attract replacements that are as skilled, knowledgeable, and committed as they are. Through this, community vitality, resilience, and adaptive capacity will be maintained or, better yet, increased.

Let's take this exploration one step further; while it is challenging, but far from impossible to look around the world and find human communities that are solidly upcycle over long periods of time, it is much more challenging to find upcycle human communities whose behavior acknowledges the reality that an upcycle human community is only as strong and successful as the ecological communities on which its sustenance depends. Given our understandable tendency to focus on our own kind more that other species, it makes sense that we grasp and commit to the goals of creating up cycle human communities more easily and readily than the same processes in ecological communities. Given the relative ease of transporting what we need and want, and our habit of overlooking the progressive, and often distant decline of the ecological systems we draw from, it makes sense that human nature makes it tough for us to conceptually link the human and the ecological into an integrated, interdependent whole. Our future depends on overcoming these hurdles and evolving into a species and cultures that recognize and prioritize the essential importance of building human communities and interdependently linked ecological communities that are all solidly up cycle.

Exploration and Analysis - Our efforts to better understand upcycle systems my be helped by considering the following pair of examples; both interweave human and ecological communities. The year is 1780; from our vantage point on the western extreme of Britany we watch a well built and expertly skippered, wooden sailing vessel clear the protection of land and reach to the southwest across a fresh northwesterly breeze. Before night fall, the ten men aboard enjoy a quick supper of cod and bread washed down with mugs of apple cider. 100 years later, we might observe an apparently identical scene - well built vessel, ten men, headed offshore into the setting sun.......

Though the two circumstances are so closely identical, by the time we watch the second departure, every mortal ingredient in the first scene no longer exists - the men dead, the vessel easily rotted away or close to it, the cotton sails long gone, the trees that grew the apples that were squeezed for the cider, fallen and rotted or burned. While all of the ingredients that make up the repeated scene will go the same way, it is possible that a third ship could be outward bound in 1980. This is a possibility because all of the individually down cycle ingredients come together to create an upcycle, potentially immortal system; oak in the keel could have grown from acorns dropped by the trees that provided keel; sailors who were the grandchildren of those who went before; cod caught from the same fishery..... and on it goes. While it may be easiest to identify and imagine the physical ingredients, we should take care not to overlook the skills, knowledge, and customs that are essential to carrying on this example of a up cycle system. Similarly, the scene above would only be possible, over many centuries, if the humans made it a priority to value and sustain the ecological systems on which the upcycle system depended - forests to provide wood, fisheries to provide food, human communities to reproduce and pass along skills and knowledge.

Returning to my awareness of how forest experiences and I shape one another, I recall a parallel view to the fictitious one sketched above. I was fortunate to find myself, miles from any road, resting on the edge of an alpine forest in the Canadian Rockies, watching two pack strings of horses, guided by a pair of capable packers, making their way across a mountain encircled meadow. I considered the ingredients - humans, horses, grass, water, leather, steel, know how ..... and observed how little in the scene differed from the systems of life and travel that served Lewis and Clark and their team roughly 200 years earlier. Mortal as each of the individual ingredients was, the system carried on with something close to immortality - much as the standing wave remains in the river's rapid even though the water which makes it continually passes on.

Being Practical - Now that we have worked to frame and explain these concepts and ideas, I'd be surprised if you haven't asked yourself "so what? why does this matter? How might it help us?". These are important questions to ask - and answer. We are a species and culture that is accustomed to meeting our needs and wants in ways that use up and degrade systems on which our life - and all life - depend. This habit, combined with the twin pressures of continuing pressures from growth in population and consumption can't help but end up badly. The goal of valuing, maintaining, and rebuilding living systems - ecological and human - matters because positive options for ourselves and those who follow depends on our making this challenging transition. Recognizing that, contrary to assumptions, it is not "the way of all things" to be downcycle - and that we have other alternatives gives use useful goals and frameworks for practical decision making, on all levels. In leading our forest business, my family and I use these frameworks in two main ways. The first is that we use them to inform and frame all of our decision making, and secondly we use them as a lens through which to learn, assess, and analyze.

As a species, we have a proven record of being able to accomplish remarkable feats when we can agree on our goals and work together to reach them. Both today and throughout its history conservation efforts have been compromised by people being much more focused on articulating what they do not want to happen than on clearly communicating what we do want. We find that this framework provides an effective way to positively articulate what we hope to achieve and contribute to on all scales – ecological and human.

For the past ten years we have used the framework outlined above in making all forest stewardship decisions - ranging from the most micro to the mast macro scale. As we plan what will be done on a stand by stand basis we ask ourselves "what approach to logging this area is most likely to create up cycle conditions?". In the years following the logging we monitor and analyze the results and compare them to what we thought might happen. Moving outward in scale, we evaluate multiple stands, making up entire sections of a forest in terms of relative progress in building upcycle conditions. In all of these cases, we ask ourselves "If we walked away from this area for several years would its value, utility, complexity, resilience to disturbance, and adaptive capacity increase over time, and by how much?". In more general ways, we also apply this same framework to the human communities that are most closely linked to our forests - "are they downcycle or upcycle?", and "what actions, taken by us or others, are most likely to build and maintain upcycle conditions?".

The second main way that we make practical use of this framework is through exploring and learning from human and ecological communities throughout the world. In this world with too many striking examples of downcycle communities, where are the best examples of places that are not, and how will we learn from them? Human communities, ecological communities, or better yet, interdependently interwoven. Elinor Ostrom's Governing the Commons provides an excellent counter to the common belief that long lived, upcycle communities do not exist and are an impossibility. Through this combination of active stewardship and broad study we've proven to ourselves that these concepts and frameworks have practical utility and reshape our ways of and interacting with the world, on all scales.

The Crux - Now we've reached the crux -the most important point. A sailing ship is a useless contraption without wind to make it useful; a locomotive is just a silent mountain of iron unless it's made animate by the addition of fire and coal. Similarly, the utility of the framework shared above is only as great as the values and ethics that we bring to making use of it. For those who believe that the earth's living systems purpose is for us to use, use up, and move on, the framework is as useless as the becalmed ship or a cold locomotive. My assertion that our common future hinges on our choosing to develop and live by new ethics is far from new. In more modern times consider Leopold's land ethic, and King's "I have a dream". Kathleen Dean Moore's recent A Great Tide Rising provides a compelling articulation of the essential role that ethical evolution must play as we confront the problems of climate change. Similarly, the utility and power of the upcycle - down cycle framework is only as great as our willingness and ability to make the necessary ethical transformation. As we individually and collectively decide the relative importance of competing priorities, we must develop and live by a life ethic that prioritizes understanding, maintaining, rebuilding, and celebrating upcycle systems - and refuses to continue to tolerate downcycle systems. We must come to accept that that no human community, small to large, can be upcycle as long as it draws is sustenance from more-than-human communities that are being degraded. Whether we are assessing the value and success of our individual lives, our businesses, our investment portfolios, home country, or species, we have the opportunity to live by a new ethic through prioritizing choices that maintain and rebuild life. While it is easy, convenient, and customary to single out and fault the farmer, rancher, or forester for their role in perpetuating downcycle conditions - "why don't they have a land ethic?" - we must learn to acknowledge that we all shape the systems that they operate within through the daily decisions that we make. As consumers, investors, and voters, our decisions help determine whether responsible stewardship is a realistic option for the growers we depend on. When I consume, invest, and vote, I work to know whether my choices are driving systems up or down. It is challenging, but possible. An increasing number of forward looking growers have already demonstrated that they are both committed to this framework and have the ethical beliefs needed to drive it; our individual and collective impact will be determined by whether the individuals who shape the larger systems of which they are a part will choose to join them in making the transition to a life affirming ethic.

We began with an overheard conversation on the steps exiting a memorial service about the "way of all things". Knowing that I'll have future opportunities to eves drop, I look forward to being surrounded by an increasing number of community members who understand and celebrate the fact that while we're each, individually as downcycle as they come, we have the chance to bring meaning and purpose to our individual and collective lives by working where we are, with the time and resources that we have, to create and benefit from upcycle systems - stationary waves in the river though which our individual lives pass. We all have dreams; these are mine.