Cheap Everything

Economies powerfully shape forests - and everything else; will we shape them to work for us?

The Answer: I admire his candor. In answer to my question, he was willing to put into words what most in our region only choose to communicate through their actions. “The needs of people, for revenue from these forests, are great enough that they should be a higher priority than keeping species in the Oregon’s North Coast forests from going locally extinct”.

The Question: In the April 22nd, 2010 meeting of Oregon’s Board of Forestry meeting I reminded fellow board members of information the department’s staff had shared with us and posed what I see to be an essential question. The context of the question is that monitoring shows that the well being of many animal species in the North Coast region that once were plentiful is now in serious decline: at least four species are locally extinct, nine are federally listed as threatened or endangered, four are listed as “sensitive, critical”, and twenty two are listed as “sensitive, vulnerable”. A total of at least 39 species in this region are either gone or in serious trouble. The question asked of fellow board members was: “Is this situation acceptable – or unacceptable?”.

While my fellow board member’s answer disappointed me, it did not surprise me. I know him to be an educated, thoughtful, generous, and community-spirited person, whose life as the leader a commercial timberland company gives him a realistic understanding of the economic, political, and cultural factors that underlie decisions about Oregon’s forests. I know also that he bears no ill will toward the 39 mammals, fish, and birds headed toward local extinction – and that he shares my knowledge that the services provided by these 39 species play important roles – as predators, pollinators, fungi spreaders, nutrient pumpers - in maintaining forest health. Understanding him and his response helps us understand our larger predicament as we struggle to maintain both land health and a functioning forest products economy. But where I believe that we can’t afford to lose these species, he believes that we can’t afford to keep them. What explains why he feels that we must choose between reliable prosperity for people and reliable prosperity for other living things?

The Cause – As a fellow owner of working forest land, I also feel the pressures, and have spent too much time trying to make sense of this problem – “why can’t we just commit to the twin goals for our region’s forests of economic health and ecological health?”. If we’re civilized, capable, ethical folk, who care about leaving behind good options for our grand children, what’s the problem with agreeing that Aldo Leopold’s goal of conservation is a logical cornerstone of our definition of success?

“When the land does well for its owner, and the owner does well by his land; when both end up better by reason of their partnership, we have conservation. When one or the other grows poorer, we do not.”

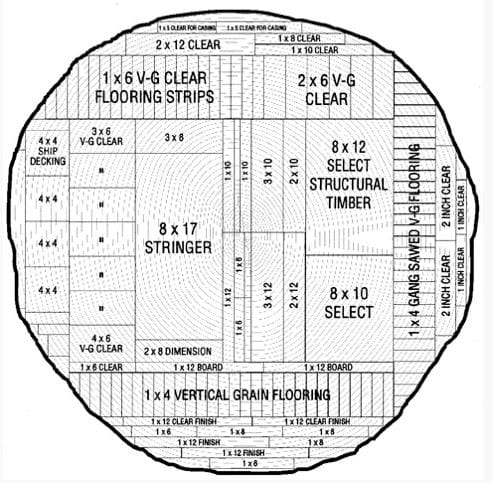

Hunting for answers, I think I found the root cause on the end of aisle twenty one at Home Depot. The sign on the stack of freshly milled 2x4’s tells me that I can buy one for $1.67. Twenty feet up aisle seven the price on the hardwood flooring from China selling for $.87/square foot adds more flesh to the story’s bones. Knowing what is involved in owning the forest, growing, logging, transporting, and milling the tree and getting the lumber sold and to market, I am baffled by how these prices can be so low. The answer lies not in what we, as forest owners, think our wood should be worth, but in the market’s message to us about how low our prices need to be if we want people to buy what our forests grow. Lumber from trees grown in our forests must compete side by side with lumber brought to us through the global market place from countries that have low – or no – standards for how forests and/or people are treated. Their wood comes to market with an artificially low price due the subsidy created by the conversion of commonwealth (well being of forests, waterways, climate, human communities…) into the vendor’s personal wealth. Cheap is an illusion that too many consumers are all too willing to ignore.

In the midst of whipping myself into an indignant froth about the tyranny of cheap wood, it occurs to me that maybe cheap wood is not the “bad news” but instead the relatively “good news”. Our forests provide many goods and services – in addition to wood - that our fellow citizens rely on – and would miss if our forests stopped providing them – including clean, cool water; maintenance of atmospheric balance through fixation of carbon dioxide and moderation of climate, habitat for species we depend on directly (EG salmon for supper), or indirectly (pollinators, predators, etc.), yet I, as a forest owner, receive no financial incentive to grow forests that keep providing these essential goods and services. I imagine the scene at the end of aisle nine where beside the lumber are boxes of forest habitat, and stored carbon, and a jug of clear, cold, clean water – all with the price tag of “FREE”. So while the bad news is that the value placed on our wood may be outrageously low, the good news is that at least it is the one thing we provide for which we are compensated.

What do these price tags of $.68 and “free” in the aisles of the big box stores have to do with the answer given by my fellow board member? If you are running a business (private or public) where you are paid nothing for much of what you provide, and a very low price for the one item for which the forest owner is paid, you will only stay in business if you work very hard to reduce your costs of operation and maximize your revenue by providing as much product as possible.

The Predicament – Pressures of the global marketplace leave US forest owners (private and public) in a predicament that my farmer friends remind me that we share with all who grow things for a living. At the same time that we might be critical of the practices in other countries because of the ways that they choose to degrade land, water, and air and/or unfairly treat people (“how can they do that?!”), we need to honestly wrestle with the reality that, due to global wood markets, the choice to degrade land and people beyond our borders creates powerful pressures to do the same within our borders. Efforts to resist the pressures – through such steps as strengthening state forest practice regulations to levels that maintain land health – can result in the choice of those controlling capital to pull their resources and reinvest it in regions “where there is still opportunity” to get a greater return on the investment. Capital leaves, mills close, loggers migrate in search of work, and without viable markets, stewards of working forests find it even harder to achieve the goals of conservation forestry. For examples of this pattern, you need look no further than California and Central and Eastern Oregon. This brings us back to my fellow board member’s belief that we need to choose between maintaining the vitality of our forest economy or maintaining elements of land health, such as native biodiversity.

The Questions – If there is a resolution of this predicament, perhaps the path leads through understanding and answering the following questions:

1. As people who shape the future of Oregon’s forests (we all do, in some way), what is our goal? Is our aim to create reliable prosperity for humans and for the other members of the living community, or only for humans?

2. If we continue on the path we are on, communicating through our actions – and inaction – that it is acceptable to build economic vitality at the expense of spending ecological capital – does this lead us to a place that we want to go?

3. What would it take to change the context so that when members of a future Board of Forestry is asked whether it is acceptable to have 39 species headed toward local extinction they can – and will – unanimously, and without hesitation, say – “of course that is not acceptable; reliable prosperity for humans is only possible if we create reliable prosperity for the living systems on which our forest businesses depend”.

I like to believe that there are solutions – because I can’t accept the other alternative. Do the solutions lie in the cultural changes of raising awareness and creating social pressure to buy local products and learn to pay the true costs? Probably. Developing regulations, such as a cap on carbon, that would drive the development of markets that would shift the price for forest services from “free” to some figure that would influence landowner stewardship? Probably. Encourage the development of a legitimate, globally applicable forest certification scheme which allows consumers to vote with their forest products buying dollar for responsible forestry? Probably.

While I believe that it is important to work on these possible solutions and others, I also believe that two essential initial steps are: 1) building a stronger, deeper, shared understanding of our predicament and the events that have created it, and 2) a shared agreement that economic prosperity that comes at the expense of land health is a path we will no longer choose.